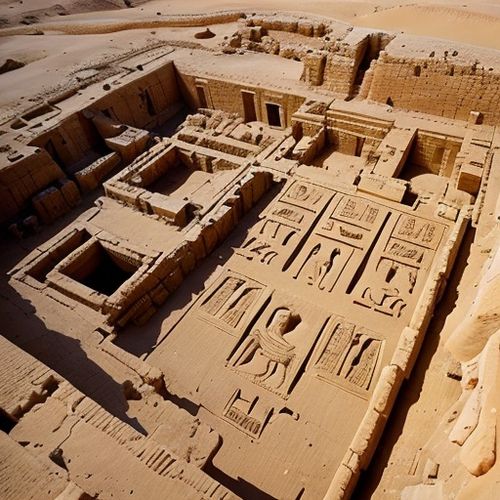

For centuries, the grandeur of the Roman Empire has fascinated historians and archaeologists alike. Among its many achievements, Rome's advanced aqueduct system stands as a testament to its engineering prowess. However, recent research suggests that this very innovation may have harbored a deadly secret – lead poisoning. The theory that Rome's elite were slowly poisoned by their own plumbing has gained traction in academic circles, painting a grim picture of unintended consequences.

The Romans were pioneers in hydraulic engineering, constructing vast networks of aqueducts to supply their cities with fresh water. Wealthy households often had private lead pipes (known as fistulae) to distribute water throughout their homes. While the Romans were aware of lead's toxicity, they believed running water prevented contamination. Modern science tells a different story.

Archaeological evidence shows significantly higher lead levels in Roman aristocratic remains compared to lower classes. The wealthy, who could afford elaborate plumbing systems, were exposed to constant low doses of lead through their drinking water and cooking vessels. This chronic exposure may explain some peculiar aspects of Roman elite behavior documented in historical records.

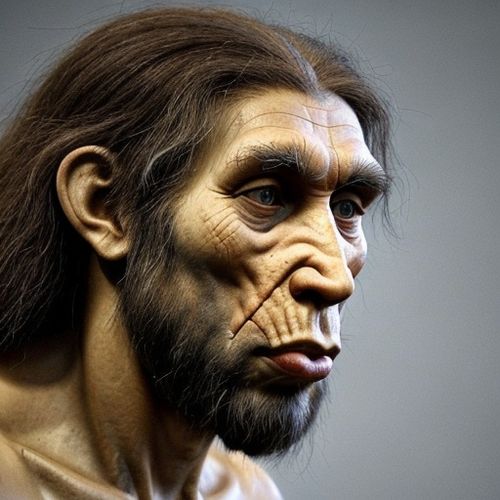

Lead poisoning manifests in various neurological symptoms that align disturbingly well with accounts of later Roman emperors. Historical descriptions of erratic behavior, cognitive decline, and irrational decisions among Rome's rulers could potentially be linked to lead-induced brain damage. The infamous madness of emperors like Caligula and Nero might have had a chemical basis rather than purely psychological origins.

Economic historians note that lead production peaked during the first and second centuries AD – precisely when some of Rome's most unstable rulers held power. The subsequent decline in lead production curiously coincides with the period historians call the "Crisis of the Third Century," when the empire nearly collapsed under a series of short-lived emperors.

Not all scholars accept the lead poisoning hypothesis. Some argue that the lead levels found in Roman remains, while elevated, weren't sufficient to cause widespread cognitive impairment. Others point out that lead exposure was likely uneven across different social classes and geographic regions. The debate continues as new archaeological techniques allow for more precise analysis of ancient remains.

What makes the lead pipe theory compelling is how it connects technological advancement with societal decline. Rome's sophisticated water system, meant to improve quality of life, may have inadvertently weakened the very class responsible for governing the empire. The parallels with modern environmental health concerns are striking – our own civilization faces similar dilemmas with industrial chemicals and pollution.

The lead hypothesis offers a cautionary tale about the unintended consequences of technological progress. As we uncover more evidence about ancient Rome's environmental health, we're reminded that civilizations can be undermined by invisible threats – not just by invading armies or economic collapse. The silent accumulation of lead in Roman bones might tell us as much about their fall as the more dramatic battles and political intrigues recorded in history books.

While we may never definitively prove that lead pipes contributed to Rome's decline, the theory serves as an important reminder of how environmental factors can shape human history in unexpected ways. As modern societies grapple with our own toxic legacies, from microplastics to forever chemicals, the story of Rome's lead pipes takes on new relevance in our understanding of civilization's fragility.

By Victoria Gonzalez/Apr 10, 2025

By Joshua Howard/Apr 10, 2025

By Noah Bell/Apr 10, 2025

By Emily Johnson/Apr 10, 2025

By Eric Ward/Apr 10, 2025

By Megan Clark/Apr 10, 2025

By Samuel Cooper/Apr 10, 2025

By Daniel Scott/Apr 10, 2025

By Emma Thompson/Apr 10, 2025

By Rebecca Stewart/Apr 10, 2025

By Lily Simpson/Apr 10, 2025

By John Smith/Apr 10, 2025

By John Smith/Apr 10, 2025

By Samuel Cooper/Apr 10, 2025

By John Smith/Apr 10, 2025

By Rebecca Stewart/Apr 10, 2025

By Joshua Howard/Apr 10, 2025